|

From February - May, 2015, I had the privilege of visiting schools across Finland. With each school visit and after every discussion relating to global education in Finland, I began to perceive the following themes that helped me to frame, understand, and articulate my observations:

|

Values of basic education in Finland

The National Core Curriculum defines underlying values of basic education as “human rights, equality, democracy, natural diversity, preservation of environmental viability, and the endorsement of multiculturalism. Basic education promotes responsibility, a sense of community, and respect for the rights of freedoms for the individual.” These values reflect Finnish culture and situates schools as a vehicle to promote students’ cultural identity as a Finn and as a citizen of the world. (1)

These core values not only intersect with but also inform the definition of global citizenship in the next National Core Curriculum 2014, to be implemented in 2016, which integrates concepts of a holistic development of a global citizen through the transversal competencies of thinking and learning to learn; taking care of oneself, managing daily activities and safety; cultural competence, interaction and expression; multiliteracy; ICT competence; participation and influencing a sustainable future; and competence for the world of work and entrepreneurship. (2)

These values and global competencies are evident everyday in Finnish classrooms, from learning the workings of school life in primary years to the formal study of modern languages. As Finland moves forward in development of curriculum and teaching strategies for a more robust and systemic expression of global citizenship education, educators begin with a sturdy foundation of ideals that are already thriving in schools.

These core values not only intersect with but also inform the definition of global citizenship in the next National Core Curriculum 2014, to be implemented in 2016, which integrates concepts of a holistic development of a global citizen through the transversal competencies of thinking and learning to learn; taking care of oneself, managing daily activities and safety; cultural competence, interaction and expression; multiliteracy; ICT competence; participation and influencing a sustainable future; and competence for the world of work and entrepreneurship. (2)

These values and global competencies are evident everyday in Finnish classrooms, from learning the workings of school life in primary years to the formal study of modern languages. As Finland moves forward in development of curriculum and teaching strategies for a more robust and systemic expression of global citizenship education, educators begin with a sturdy foundation of ideals that are already thriving in schools.

|

|

Finns have a vital connection to nature. U.S. Ambassador to Finland Bruce Oreck describes how, "It is the relationship of citizens with their natural surroundings that creates the unique 'essence' of the country. Finns are connected to nature in a way that feels built into their DNA.This connection has had a profound cultural impact on the way Finns interact with the world. It is this connection that makes Finland special." (3) Finnish students are often outside, practicing and living values, attitudes and skills essential to leading a sustainable life.

Photo: 2nd grade students in western Finland |

|

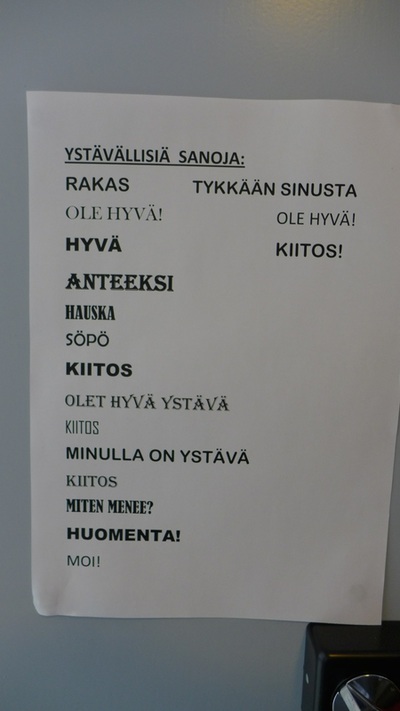

A primary school in rural, central Finland incorporates intercultural competencies through the study of Finnish Sami peoples in a 1-2 combination class. "Polite" words are displayed on the classroom door to support students' acquisition of social skills that are foundational to global citizenship competencies.

|

|

|

|

Students begin to learn English in 3rd grade and study through 9th grade. Swedish (the national second language) instruction begins for Finnish-speaking Finns in the 7th grade and students can study another modern language beginning in lower secondary school. Choices often include French, German, Spanish, and Russian. Multilingualism is a hallmark of Finnish education that enables its citizenry to be global participants. The first graders at this school in Jyväskylä were reviewing animals and animals sounds in English. The teacher began her 8th grade English class with the task of drawing a house. As she predicted, students' houses were similar with a triangle roof and square base. She used her experiences living in Nepal to describe and illustrate how houses there differ from their perceived notion of a house.

|

|

Ethics and religion education offer opportunities for students to learn about cultures through the study of world religion. These classes offer a natural, supportive venue for the developmnet of values, attitudes, knowledge and skills to be a global citizen. This 8th grade class in Espoo was studying Hinduism. During this 75-minute class, students worked in small groups to complete slideshow presentations about various aspects of Hinduisum then presented their work to the class. Students were assessed on the product and the process of working together which the teacher asked the students to reflect and share with the class.

|

Articulation of curriculum through national, municipal, and school priorities -

Meet Vesilahti Lower Secondary School

Meet Vesilahti Lower Secondary School

|

My visit to Vesilahti began at 6am when I boarded a train from Jyväskylä to Tampere followed by a 45-minute bus ride. I arrived at almost 10am to a warm welcome by Tapani Pietilä, the rhetori of the school. Two 7th grade students gave me a tour of the campus, equipped with keys so they could show me behind all doors. We sat down to cake, coffee and conversation in the Teacher Room. a venue I returned to throughout the day for coffee and chats with teachers. At 11 we met with the 9th grade class for our first session; we met together again at the end of the day.

|

|

|

The lower secondary school in Vesilahti prides itself on being a "global school."

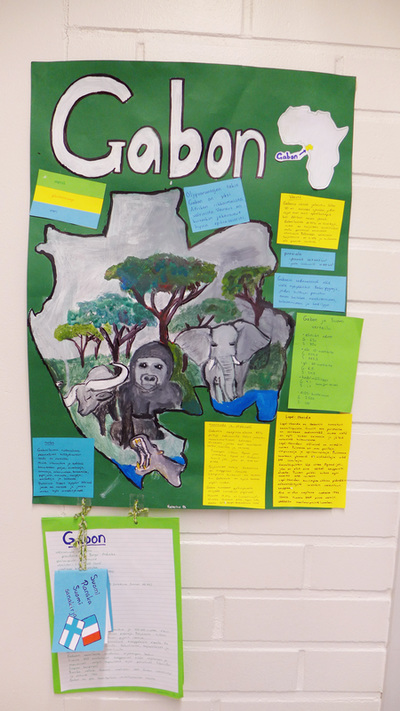

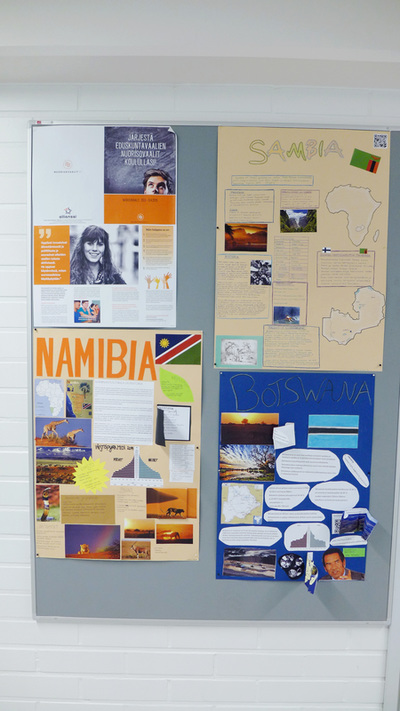

In my experiences and conversations with educators, I’ve heard that the National Core Curriculum does not dictate what or how teachers teach or priorities municipalities or schools set. So, while there is - from my point of view - a level of uniformity among schools, there is room for innovation. At Vesilahti Lower Secondary School, that innovator is their head teacher/ administrator, Tapani Pietilä, who founded the school 24 years ago. On the day I visited, teacher after teacher spoke about how Mr. Pietilä is the energy behind the global education initiatives at this school. He hires teachers who will thrive in this environment and who will be part of this teaching and learning community. Mr. Pietilä is dynamic, energetic, and exudes caring and respect for his students. During my visit, he facilitated two class sessions with 9th graders during which the students shared their global education experiences at this school. The interaction between Mr. Pietilä and the students is easy and filled with humor, respect, and shared experiences. Mr. Pietilä began the conversation with a summary of global education at Vesilahti, “Global education does not need to be international. It starts in our neighborhood. We need to know ourselves and each other first.” All students are invited to participate in international exchanges and projects and there are multiple opportunities for students to fund raise for these experiences, but students who do not go on an exchange are not exempt from global citizenship learning. Besides school-based opportunities (for example, this year, the school held a United Nations forum in which each student at the school represented one of the UN countries; this project was integrated throughout content and involved weeks of research, production, and collaboration) there is great emphasis is on developing values, skills and attitudes that support students being global citizens. As one student shared, “We understand culture better. We know that the way we live is not the only way to live.” Vesilahti is a special school that is ripe with examples of how global education, global citizenship, development education, and democratic education can offer potent educational and life experiences to students. Development education has been a focus of Vesilahti. In particular, the school has worked with a school in Vietnam, a school in Zambia and a school in Senegal to support development to improve lives of students in communities. The school fund raises thousands of dollars each year to help support specific projects. For example, in Zambia students have funded the building of a health center and the education of a young woman from the village to be educated as a nurse; building 2 houses for teachers to attract and maintain qualified teachers in the village; and electricity for the school. On the Finnish side, students from Vesilahti coordinate fund raising and accounting, setting expectations for the schools for prompt reporting of receipts. The school they worked with in Vietnam relayed that they are now at the point of independence; support from Finland is no longer necessary, and they are excited to continue to develop the relationship with Vesilahti in this new way. Students have traveled to Vietnam, Senegal, and Zambia to witness the progress, to learn about cultures, and to interact with students, teachers and community members. As one student shared of her experience visiting Zambia, “We know that people are there. But through these exchanges, I really know they ARE there.” Mr. Pietilä has fostered decades-long relationships with schools throughout the world - Zambia, Senegal, Germany, Latvia, Greece - and he usually travels with students on these exchanges. While I was walking in the hall with him, he received a call from the teacher from Senegal and launched into the conversation in fluent French. Mr. Pietilä lives global and mirrors his vision, passion, and being to the students and teachers. Mr. Pietilä is humble and points to his students and teachers, but it’s evident that his influence and work is foundational. So, when he revealed that he will retire after one more year, I had to ask, “What will happen to these programs?” In Mr. Pietilä’s view, he does not know. He feels that it is up to the new principal and her/ his work with the faculty and student body. But he and teachers with whom I spoke with admitted that these initiatives could be gone when he retires. |

Below: The European Union, U.S., and Finnish flags were flying to greet me.

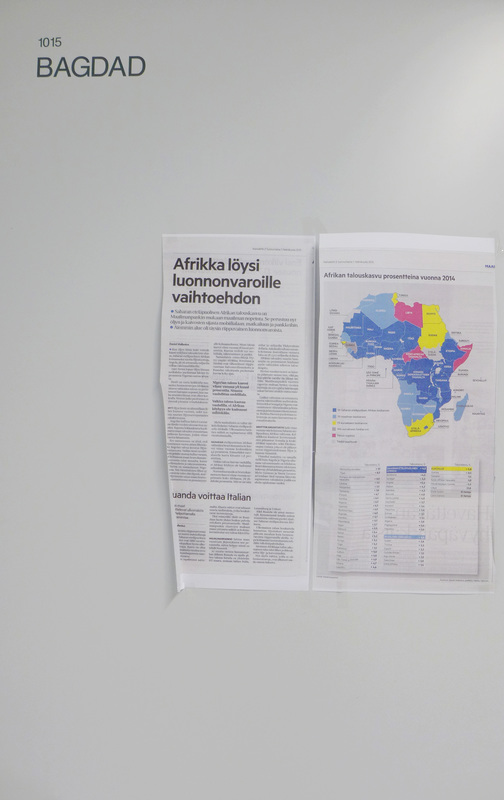

Below: All of the rooms at the school are named after cities of the world. Tepani shared how he likes to tell parents, particularly, to go to Baghdad, for example. Community members can travel the world here.

Below: The hallways are brimming with student work from the United Nations project. The school held a United Nations forum in which each student at the school represented one of the UN countries; this project was integrated throughout content and involved weeks of research, production, and collaboration.

|

Below: Artifacts from projects with students from around the world.

Teacher Autonomy:

Meet Kasavuoren Lower Secondary School & Mankolan Lower Secondary School

At Kasavuoren Lower Secondary School in Espoo, educators employ a shared leadership model in which all teachers are on a 'goal team' that focuses on one of the school's 7 core goals, including the Internationalization Unit. Global education is one dimension of innovation that thrives at this grade 7 - 9 school. The school supports a student parliament with student committees that make decisions about school life. They have, for example, implemented a recycling program and have been studying how to reduce food waste at lunch. An annual theme is chosen as an inspiration for the year; this year's theme has been 'creativity.' Teachers and students have been encouraged to demonstrate creativity through a variety of ways, including students painting bathroom facilities in the school.

While there exists a climate of innovation, there are no direct mandates on teachers on how or what to do to meet expectations around global education or the yearly theme. This is in keeping with the professionalism afforded to teachers in Finland.

Marjo Kikki, an English and Swedish teacher, and Päivi Rohkimainen, Ethics and Religion teacher, have worked for years fostering a partnership with a school in Tanzania. For their Finnish students, the objective is to broaden perspectives and to encourage students to appreciate the values and way of life of another culture. Students and teachers travel to and from Tanzania every other year. Students at Kasavuoren particiipte in work days throughout the year, and funds raised support their exchange school in Tanzania with the purchase of learning materials and building infrastructure. Ms. Kikki and Ms. Rohkimainen encourage students who are motivated, open-minded and committed to working to make a difference to apply for the biennial exchange. They reflected how students often return from this life-changing experience with ideas for their future study, a sense of confidence, and a desire to help people in different ways.

In addition to the exchange in Tanzania, students have participated in an exchange to China and has long-standing relationships through exchanges with schools in Holland and Germany. While these experiences are often showcased in the community, Ms. Kikki and Ms. Rohkimainen understand that exchanges are a small part of their school-based internationalization efforts and that becoming a global citizen begins in school and in the community. There is a school-wide commitment to students seeing themselves as a part of the world and active participants in local and global settings.

While there exists a climate of innovation, there are no direct mandates on teachers on how or what to do to meet expectations around global education or the yearly theme. This is in keeping with the professionalism afforded to teachers in Finland.

Marjo Kikki, an English and Swedish teacher, and Päivi Rohkimainen, Ethics and Religion teacher, have worked for years fostering a partnership with a school in Tanzania. For their Finnish students, the objective is to broaden perspectives and to encourage students to appreciate the values and way of life of another culture. Students and teachers travel to and from Tanzania every other year. Students at Kasavuoren particiipte in work days throughout the year, and funds raised support their exchange school in Tanzania with the purchase of learning materials and building infrastructure. Ms. Kikki and Ms. Rohkimainen encourage students who are motivated, open-minded and committed to working to make a difference to apply for the biennial exchange. They reflected how students often return from this life-changing experience with ideas for their future study, a sense of confidence, and a desire to help people in different ways.

In addition to the exchange in Tanzania, students have participated in an exchange to China and has long-standing relationships through exchanges with schools in Holland and Germany. While these experiences are often showcased in the community, Ms. Kikki and Ms. Rohkimainen understand that exchanges are a small part of their school-based internationalization efforts and that becoming a global citizen begins in school and in the community. There is a school-wide commitment to students seeing themselves as a part of the world and active participants in local and global settings.

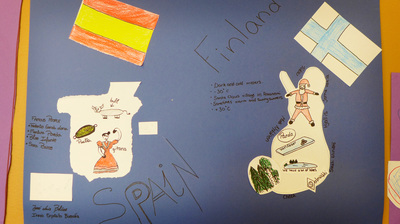

While vacationing in Spain a few years ago, Marjut Hiltunen met an English teacher from the Ave Maria’s School in Granada and struck up a conversation. A couple of years later, Ms. Hiltunen and her students welcomed twenty Spanish students and 2 teachers to Finland in March, 2015.

A Spanish, English and Swedish teacher at Mankolan Lower Secondary School in Jyväskylä, Ms. Hiltunen strives to make learning a foreign language relevant, authentic and engaging for her students.

I had the opportunity to spend a day with the Finnish and Spanish students at Mankolan. Already in the middle of their visit, Spanish students were staying in Finnish host families, had already been skiing at Laajavouri with their new Finnish friends, and, the next day, all the students and teachers were staying the night in a cabin and going ice swimming. It was evident how quickly the students fell into friendship; it was fascinating observing students from Spain speaking with Finnish students primarily in English.

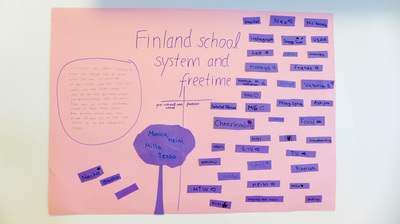

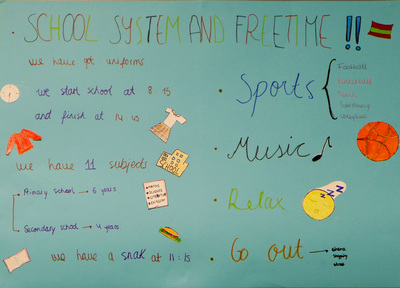

I followed a group of Spanish students early in the morning to the primary school where they presented to third grade English classes about their culture and city. Then, I observed Finnish and Spanish students engaged in a cultural exchange activity, describing the schools systems in Finland and Spain and describing free time for teens in each country. Ms. Hiltunen promptly displayed students' work along side the work they'd done that morning, comparing Finnish and Spanish culture. After lunch, students met in the home economic classrooms to cook and eat together. Mixed-groups were given three recipes for 2 Finnish dishes and 1 Spanish dish, written in Finnish and, therefore, requiring communication and collaboration. Students worked purposefully and joyfully while their teachers observed how this cross-cultural exchange came about organically after that fated meeting in Granada. The teachers and students from Ave Maria's School were looking forward to welcoming their new Finnish friends to Granada a the end of May.

A Spanish, English and Swedish teacher at Mankolan Lower Secondary School in Jyväskylä, Ms. Hiltunen strives to make learning a foreign language relevant, authentic and engaging for her students.

I had the opportunity to spend a day with the Finnish and Spanish students at Mankolan. Already in the middle of their visit, Spanish students were staying in Finnish host families, had already been skiing at Laajavouri with their new Finnish friends, and, the next day, all the students and teachers were staying the night in a cabin and going ice swimming. It was evident how quickly the students fell into friendship; it was fascinating observing students from Spain speaking with Finnish students primarily in English.

I followed a group of Spanish students early in the morning to the primary school where they presented to third grade English classes about their culture and city. Then, I observed Finnish and Spanish students engaged in a cultural exchange activity, describing the schools systems in Finland and Spain and describing free time for teens in each country. Ms. Hiltunen promptly displayed students' work along side the work they'd done that morning, comparing Finnish and Spanish culture. After lunch, students met in the home economic classrooms to cook and eat together. Mixed-groups were given three recipes for 2 Finnish dishes and 1 Spanish dish, written in Finnish and, therefore, requiring communication and collaboration. Students worked purposefully and joyfully while their teachers observed how this cross-cultural exchange came about organically after that fated meeting in Granada. The teachers and students from Ave Maria's School were looking forward to welcoming their new Finnish friends to Granada a the end of May.

Collaborative approaches to considering global education, defining global competencies, and formalizing policy

For the first time, the National Core Curriculum 2014 will define global education and competencies as guiding principles for educators. The creation of competencies and policy has been a process over decades and through collaboration through international collaborative initiatives with, among others, the United Nations, UNESCO, and the European Union.

As described above, global citizenship eduction is inherently embedded in Finnish curricula, and many schools across the country have furthered students' exposure and experience through international projects. One influential initiative was the European Union's Lifelong Learning Programme that, "was designed to enable people, at any stage of their life, to take part in stimulating learning experiences, as well as developing education and training across Europe. (5) Thousands of students across Europe, including Finland, participated in the Comenius program through which students and teachers could participate in exchanges across Europe through the project goals that included

From 2007 - 20110, Over 25,000 schools participated in Comenius projects impacting over 130,000 teacher and students (8)

Between 2007 and 2010, the action led to cooperation between almost 26,000 schools and financed over 130,000 pupil and teacher mobilities per year.

I visited schools across Finland who had been connected with and have maintained relationships with school through Comenius projects in the Netherlands, Poland, Germany, and the UK. The current project of the European union is ERASMUS + that "will provide opportunities for over 4 million Europeans to study, train, gain work experience and volunteer abroad." (6) For primary and secondary schools, ERASMUS + "aims to improve the quality of teaching and learning from pre-primary through to secondary level in schools across Europe." (7) Schools must apply for this 3-year program that allows them to be in a network of schools that represent diverse countries across the European Union.

As described above, global citizenship eduction is inherently embedded in Finnish curricula, and many schools across the country have furthered students' exposure and experience through international projects. One influential initiative was the European Union's Lifelong Learning Programme that, "was designed to enable people, at any stage of their life, to take part in stimulating learning experiences, as well as developing education and training across Europe. (5) Thousands of students across Europe, including Finland, participated in the Comenius program through which students and teachers could participate in exchanges across Europe through the project goals that included

- Improve and increase the mobility of pupils and staff across the EU

- Enhance and increase school partnerships across the EU

- Encourage language learning, ICT for education, and better teaching techniques

- Enhance the quality and European dimension of teacher training

- Improve approaches to teaching and school management (5)

From 2007 - 20110, Over 25,000 schools participated in Comenius projects impacting over 130,000 teacher and students (8)

Between 2007 and 2010, the action led to cooperation between almost 26,000 schools and financed over 130,000 pupil and teacher mobilities per year.

I visited schools across Finland who had been connected with and have maintained relationships with school through Comenius projects in the Netherlands, Poland, Germany, and the UK. The current project of the European union is ERASMUS + that "will provide opportunities for over 4 million Europeans to study, train, gain work experience and volunteer abroad." (6) For primary and secondary schools, ERASMUS + "aims to improve the quality of teaching and learning from pre-primary through to secondary level in schools across Europe." (7) Schools must apply for this 3-year program that allows them to be in a network of schools that represent diverse countries across the European Union.

|

Above: Student work from an ERASMUS+ project.

|

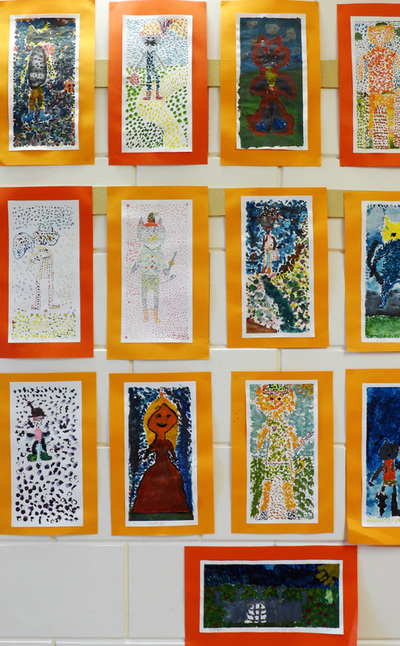

Vaajakummun koulu in Jyväskylä participates in the ERASMUS + program. Teachers from Vaajakummun participate with teachers from schools in France, Spain, Britain, Poland, Romania, Sweden, and the Netherlands. Over three years, teachers will meet for professional development work in each at each of the host schools. This spring, for example, this network of teachers met in France and Spain. Through collaborative work, teachers organize interdisciplinary, cultural projects to take back to their schools. My first visit to Vaajakummun was just a couple of weeks after collaboration in France. When I returned in May, I had the opportunity to see work the students from Vaajakummun created based on the project that included younger students reading Puss and Boots and creating impressionist-style art from their reading. Schools post student work on an online, secure portal through which students and teachers can collaborate.

|

UNESCO Associated Schools, "work in support of international understanding, peace, intercultural dialogue, sustainable development and quality education in practice." (9)

UNESCO Associated Schools, "work in support of international understanding, peace, intercultural dialogue, sustainable development and quality education in practice." (9)

I also encountered Finnish schools that are part of the UNESCO Associated Schools Project Network, a global network of over 10,000 schools in 181 countries that are

- engaged in fostering and delivering quality education

in pursuit of peace, liberty, justice and human development

- in order to meet the pressing educational needs of children and young people

throughout the world. (9)

I met with the coordinator, Anne Streng, of the project at the Norssi primary school in Jyväskylä, who helped bring the program to this school 20 years ago. Ms. Streng shared that UNESCO provides the schools with the opportunities to try out new approaches, to test UNESCO learning materials, to promote new ways to teach and study, and to connect students to global questions.

- engaged in fostering and delivering quality education

in pursuit of peace, liberty, justice and human development

- in order to meet the pressing educational needs of children and young people

throughout the world. (9)

I met with the coordinator, Anne Streng, of the project at the Norssi primary school in Jyväskylä, who helped bring the program to this school 20 years ago. Ms. Streng shared that UNESCO provides the schools with the opportunities to try out new approaches, to test UNESCO learning materials, to promote new ways to teach and study, and to connect students to global questions.

An integrated approach to establishing global education as being central to learning:

Meet Seinäjoki Upper Secondary School

Meet Seinäjoki Upper Secondary School

At Seinäjoki Upper Secondary School, I observed evidence of a beautiful model of teacher collaboration to integrate content areas through global lens. When I think about how global education can be seamlessly brought to students, this is what it looks like.

There has not been a mandate for teachers to work together, rather, this group of teachers came together after a professional development opportunity in which they had time to talk to each other. They realized that through their content areas, they were teaching common topics and themes. Through their own initiative, they have developed a global education course.

The course itself is a 6-week study that integrates studies, classes and requirements for Economics, Ethics, Geography, Health Science, and Art. The teachers have identified weekly themes (for example, population, human rights, war and crisis) and that theme is taught through each subject area. This course is offered to first year students and they engage in this six-week study as a cohort, which is quite unusual.

I had the opportunity to spend a day with this cohort of students and their teachers. The topic for the week was population, and throughout the day, students were engaging in content around this theme through economic development (Economics), urbanization (Geography,) and human rights (Ethics.) Additionally, in their Health Science class, students were preparing for a community engagement experience for the next day. The other subject in this course is art, which meets on different days. The current project in art, related to the themes of the global class, involves creation of anti-ads - a media literacy component.

The students remained in the one classroom throughout the day for all courses, yet student engagement was consistently high. I attribute this to the following factors: (a) dynamic teachers who demonstrated enthusiasm for the content and relationships with the students; (b) buy-in from students since this was a chosen course of study; and (c) a diversity of learning activities in which students were involved.

The day began with Economics during which activities included current events reporting, discussion, the concept of salaries under varying conditions, use of computers to access text-based materials including a note-taking function; and self-study for test in geography class.

In Health Science, students spent most of their time working in small groups in preparation for their class visit to a retirement home the next day. Students had agency to choose and organize activities for residents between the ages of 70 - 100 years old (activities included stretching, singing, music, drawing, and games.) All groups reported to the class about their plans for the next day which prompted the class to practice singing a traditional Finnish song.

Students began geography class with an online test on European countries. Focusing on the topic of urbanization, students viewed images (the teacher showed 12) and made inferences about the advantages and disadvantages of living in cities. Students brought up issues around infrastructure, energy, water, housing, population, poverty, access to nature, pollution, religion, diversity, jobs, food, homelessness, arts, culture, beauty, education, technology, equity, equality, transportation, public, access, tourism, economy, service jobs, and business centers.

The day concluded with Ethics class and consideration of human rights. Students participated in a take-a-stand game, agreeing (stand up) or disagreeing (sit down) with statements read by the teacher. Statements included (a) your country’s problems should be solved before you help other countries (b) those who are healthy should be in charge of those who are not. (c) It’s useless to work towards equality because it’s not going to happen anyway. (d) It’s great to be born in Finland (this was the only question for which all students stood.)

Students pondered the dynamic between individuality and responsibility before considering this question: what is a good society? In small groups, students brainstormed then shared out their ideals for a good society (incidentally, many of the ideals are represented in Finnish society.) The teacher showed a short video produced by the United Nations which featured the idea that every human has rights. Then, working in groups, students were asked to create a rights pyramid using the articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Each group was given an envelope with cards on which articles were printed. After each group constructed their pyramid, groups shared their top choices. Working as a class, data was aggregated to show that the most important concepts according to members of the class were life, freedom, food, name and identity, and knowledge.

I had the chance to speak with the art educator who described work students were doing in her class. First, they were constructing anti or counter ads, described by the Media Literacy Project as, "parodies of advertisements, delivering more truthful or constructive messages using the same persuasion techniques as real ads. By creating counter-ads, students apply media literacy skills to communicate positive health messages." (5) Students were also creating drawings based on the study of human rights and, particularly, children’s rights. That Friday, the class would address “Fashion Revolution Day,” an annual event inspired by the Bangladeshi fire in a garment warehouse that seeks to promote awareness of where and how clothes are produced. For the end of the course project in art, students will screen print shirts and cloth bags with images and words to represent their understanding of human rights.

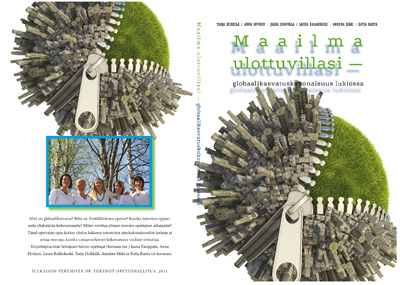

My day with the class and teachers was was an exercise in enjoying the shade of a beautiful tree that has deep roots. This group of teachers, with the support and encouragement of their administration and colleagues, has worked to create this opportunity over several years. When they participated in the “As Global Citizens in Finland” project, they came to the table with experience and an exemplary example of phenomenon-based learning, a strategy that is being highly promoted through the National Core Curriculum 2014. Through their collaborative work, this group of teachers has authored a book to share the process of creating an integrated program for global learning.

While these dedicated teachers advocate for time during the school day to meet and plan, they have recognized that the hours needed for this type of project exceed what is available during the school day. Yet, they understand that the benefits in student learning and through creative teaching, are worth it.

There has not been a mandate for teachers to work together, rather, this group of teachers came together after a professional development opportunity in which they had time to talk to each other. They realized that through their content areas, they were teaching common topics and themes. Through their own initiative, they have developed a global education course.

The course itself is a 6-week study that integrates studies, classes and requirements for Economics, Ethics, Geography, Health Science, and Art. The teachers have identified weekly themes (for example, population, human rights, war and crisis) and that theme is taught through each subject area. This course is offered to first year students and they engage in this six-week study as a cohort, which is quite unusual.

I had the opportunity to spend a day with this cohort of students and their teachers. The topic for the week was population, and throughout the day, students were engaging in content around this theme through economic development (Economics), urbanization (Geography,) and human rights (Ethics.) Additionally, in their Health Science class, students were preparing for a community engagement experience for the next day. The other subject in this course is art, which meets on different days. The current project in art, related to the themes of the global class, involves creation of anti-ads - a media literacy component.

The students remained in the one classroom throughout the day for all courses, yet student engagement was consistently high. I attribute this to the following factors: (a) dynamic teachers who demonstrated enthusiasm for the content and relationships with the students; (b) buy-in from students since this was a chosen course of study; and (c) a diversity of learning activities in which students were involved.

The day began with Economics during which activities included current events reporting, discussion, the concept of salaries under varying conditions, use of computers to access text-based materials including a note-taking function; and self-study for test in geography class.

In Health Science, students spent most of their time working in small groups in preparation for their class visit to a retirement home the next day. Students had agency to choose and organize activities for residents between the ages of 70 - 100 years old (activities included stretching, singing, music, drawing, and games.) All groups reported to the class about their plans for the next day which prompted the class to practice singing a traditional Finnish song.

Students began geography class with an online test on European countries. Focusing on the topic of urbanization, students viewed images (the teacher showed 12) and made inferences about the advantages and disadvantages of living in cities. Students brought up issues around infrastructure, energy, water, housing, population, poverty, access to nature, pollution, religion, diversity, jobs, food, homelessness, arts, culture, beauty, education, technology, equity, equality, transportation, public, access, tourism, economy, service jobs, and business centers.

The day concluded with Ethics class and consideration of human rights. Students participated in a take-a-stand game, agreeing (stand up) or disagreeing (sit down) with statements read by the teacher. Statements included (a) your country’s problems should be solved before you help other countries (b) those who are healthy should be in charge of those who are not. (c) It’s useless to work towards equality because it’s not going to happen anyway. (d) It’s great to be born in Finland (this was the only question for which all students stood.)

Students pondered the dynamic between individuality and responsibility before considering this question: what is a good society? In small groups, students brainstormed then shared out their ideals for a good society (incidentally, many of the ideals are represented in Finnish society.) The teacher showed a short video produced by the United Nations which featured the idea that every human has rights. Then, working in groups, students were asked to create a rights pyramid using the articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Each group was given an envelope with cards on which articles were printed. After each group constructed their pyramid, groups shared their top choices. Working as a class, data was aggregated to show that the most important concepts according to members of the class were life, freedom, food, name and identity, and knowledge.

I had the chance to speak with the art educator who described work students were doing in her class. First, they were constructing anti or counter ads, described by the Media Literacy Project as, "parodies of advertisements, delivering more truthful or constructive messages using the same persuasion techniques as real ads. By creating counter-ads, students apply media literacy skills to communicate positive health messages." (5) Students were also creating drawings based on the study of human rights and, particularly, children’s rights. That Friday, the class would address “Fashion Revolution Day,” an annual event inspired by the Bangladeshi fire in a garment warehouse that seeks to promote awareness of where and how clothes are produced. For the end of the course project in art, students will screen print shirts and cloth bags with images and words to represent their understanding of human rights.

My day with the class and teachers was was an exercise in enjoying the shade of a beautiful tree that has deep roots. This group of teachers, with the support and encouragement of their administration and colleagues, has worked to create this opportunity over several years. When they participated in the “As Global Citizens in Finland” project, they came to the table with experience and an exemplary example of phenomenon-based learning, a strategy that is being highly promoted through the National Core Curriculum 2014. Through their collaborative work, this group of teachers has authored a book to share the process of creating an integrated program for global learning.

While these dedicated teachers advocate for time during the school day to meet and plan, they have recognized that the hours needed for this type of project exceed what is available during the school day. Yet, they understand that the benefits in student learning and through creative teaching, are worth it.

|

Above: Six teachers from Seinäjoki wrote a book about their work integrating global studies into their content areas. Maailma ulottuvillasi —globaalikasvatuskokonaisuus lukiossa was published in 2011 and can be read as a PDF (in Finnish) at http://files.kotisivukone.com/seinajoenlukio.palvelee.fi/glob_open_opas.pdf

|

Above: One of my favorite activities I saw in Finland, Laura Kalliokoski, Ethics teacher, posted a world map on a class bulletin board. Students were invited to place orange strips on places they'd like to visit. Then, they annotate the map with flags when a country is addressed in authentic discussion inspired by the content. This photo was taken during Week 2 of the course; I wonder what it looked like at the end of the six weeks.

|

Commitment to equality

When I consider my future accounts of Finnish education, I will always start and end with Finland's commitment to equality. Section 6 of the Constitution of Finland defines this commitment: Everyone is equal before the law.

No one shall, without an acceptable reason, be treated differently from other persons on the ground of sex, age, origin, language, religion, conviction, opinion, health, disability or other reason that concerns his or her person.

Children shall be treated equally and as individuals and they shall be allowed to influence matters pertaining to themselves to a degree corresponding to their level of development.

Equality of the sexes is promoted in societal activity and working life, especially in the

determination of pay and the other terms of employment, as provided in more detail by an

Act. (11)

Jukka Sarjala, former director general of Finland’s National Board of Education, puts this national value into context in education, “Equality in opportunities and outcomes is what drives the first nine years of schooling. The national core curriculum for those nine years is challenging, but only about 4 percent of special education students attend separate schools. The rest have the capacity to be on grade level—as long as we provide expert teaching, intensive supports, and frequent remediation, as well as health and welfare services.” (12)

The commitment to equality for its citizenry extends to Finland’s vision for global education through education with conviction and in solidarity with countries that also value human rights as being fundamental to the human experience.

No one shall, without an acceptable reason, be treated differently from other persons on the ground of sex, age, origin, language, religion, conviction, opinion, health, disability or other reason that concerns his or her person.

Children shall be treated equally and as individuals and they shall be allowed to influence matters pertaining to themselves to a degree corresponding to their level of development.

Equality of the sexes is promoted in societal activity and working life, especially in the

determination of pay and the other terms of employment, as provided in more detail by an

Act. (11)

Jukka Sarjala, former director general of Finland’s National Board of Education, puts this national value into context in education, “Equality in opportunities and outcomes is what drives the first nine years of schooling. The national core curriculum for those nine years is challenging, but only about 4 percent of special education students attend separate schools. The rest have the capacity to be on grade level—as long as we provide expert teaching, intensive supports, and frequent remediation, as well as health and welfare services.” (12)

The commitment to equality for its citizenry extends to Finland’s vision for global education through education with conviction and in solidarity with countries that also value human rights as being fundamental to the human experience.

(1) National Core Curriculum for Basic Education (2004): Finnish National Board of Education. Available in English at http://www.oph.fi/english/curricula_and_qualifications/basic_education

(2) Jääskeläinen, L. (2015). Global education in the Finnish basic education curriculum reform. [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from

http://www.lvjc.lt/uploads/File/KONFERENCIJOS/GLOBALUS%20SVIETIMAS%202015%2004%2016/PRANESIMAI/J%C3%A4%C3%A4skel%C3%A4inen%20Global%20Education%20in%20the%20Curriculum%20Reform%20Vilnius130142015.pptx.

(3) Orek, B. (2013, January 29). Op-Ed. Lapin Kansa. Retrieved from http://photos.state.gov/libraries/finland/788/pdfs/Lapin_Kansa_Op-Ed_English.pdf.

(4) Sahlberg, P. (2015). Finnish Lessons 2.0: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland? New York, NY: Teachers College, Columbia University.

(5) http://ec.europa.eu/education/tools/llp_en.htm

(6) http://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/discover/index_en.htm

(7) http://ec.europa.eu/education/opportunities/school/index_en.htm

(8) http://www.mobilnost.hr/prilozi/05_1355304110_PA_impact_study.pdf

(9) http://www.unesco.org/new/en/education/networks/global-networks/aspnet/about-us/mission/

(10) http://www.medialiteracy.net/pdfs/counter_ads.pdf

(11) http://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/1999/en19990731.pdf

(12) Sarjala, J. 2013, Spring. Equality and Cooperation: Finland's Path to Excellence. American Educator. Retrieved from http://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Sarjala.pdf